In traditional Wachiperi cosmology, the energy that makes up all living things circulates constantly. All life forms share the same beginnings and are interconnected on an underlying spiritual dimension. It is in this dimension that the distinct life cycles are shaped, and disruptions in the energy flows are reflected in the physical universe. Understanding this principle is key for establishing a good relationship with forest animals and plants in the physical and spiritual realms. As a result of increased contact with Western society, however, much of their traditional knowledge about medicinal plants and cultural traditions has been lost, as well as perceptions about society and the environment, something which is particularly evident among the younger generation. This article seeks to preserve part of that traditional knowledge and cultural heritage of this group.

In traditional Wachiperi cosmology, the energy that makes up all living things circulates constantly. All life forms share the same beginnings and are interconnected on an underlying spiritual dimension. It is in this dimension that the distinct life cycles are shaped, and disruptions in the energy flows are reflected in the physical universe. Understanding this principle is key for establishing a good relationship with forest animals and plants in the physical and spiritual realms. As a result of increased contact with Western society, however, much of their traditional knowledge about medicinal plants and cultural traditions has been lost, as well as perceptions about society and the environment, something which is particularly evident among the younger generation. This article seeks to preserve part of that traditional knowledge and cultural heritage of this group.

Introduction

The community of Queros is located near the town of Pillcopata, in the Manu Biosphere Reserve. This is an area that holds many attractions for the visitor, not only interesting wild animals and plants, but also the possibility of visiting indigenous villages and interacting with the native population.

Understanding the way of life of indigenous peoples requires getting familiar with the sociocultural processes that this population has experienced in the recent past. In this way, one can better understand the perspectives of indigenous peoples, their current expectations and emerging trends.

This publication seeks to contribute to the understanding of Queros, a community of Wachiperi ancestry, particularly in terms of their cultural heritage and use of natural resources. The aim is also to help in the preservation of the traditional knowledge and culture of this indigenous group.

Social Context

Throughout the last few decades, many inhabitants of Queros abandoned their community and moved to other locations in the area, mostly Pillcopata and the native community of Shintuya. Both of these places have significant commercial activity due to the presence of a road to the city of Cusco.

Many residents of Queros left their community in search of improved opportunities for income and employment, seek better education for their children, among other motives. This process led to social disintegration and the progressive loss of the group’s ancestral knowledge, as evidenced by the lack of continuity of this knowledge in their daily practices, and by the absence of a significant transfer of knowledge, due primarily to the lack of interest among the younger generations in the cultural traditions of their ancestors.

Emigration and the lack of continuity in their traditional practices placed the community in danger of extinction. At the same time, this situation encouraged a process of internal reflection regarding the need to establish mechanisms to resist this cultural decline, which has led to the development of a proposal that reflects the interests of the community. This proposal involves the development of a community-based tourism project, which would enable its members to not only generate income and improve their quality of life, but also to stimulate a greater appreciation of their cultural values, thereby reaffirming their ethnic identity and promoting group cohesion.

General Information

The Community of Queros is located in the multi-use area of the Manu Biosphere Reserve, in the district of Kosñipata, province of Paucartambo, department of Cusco, Peru. The residents of Queros are Wachiperi, of the Harakmbut family, a group of people that has been greatly reduced in size.

The Wachiperi have lived in this area for more than a thousand years, conducting commercial trade with the Incas and establishing peaceful alliances with the Matsiguenga and the Amarakaeri of the region. In the middle of the twentieth century, a group of missionaries brought the Wachiperi together, causing a small pox epidemic that killed approximately 65% of the population (Pinasco 2002).

In 2004, the population of the native community of Queros was approximately 36 people, a very small number, which was due primarily to the increasing number of families that abandoned the area in previous years.

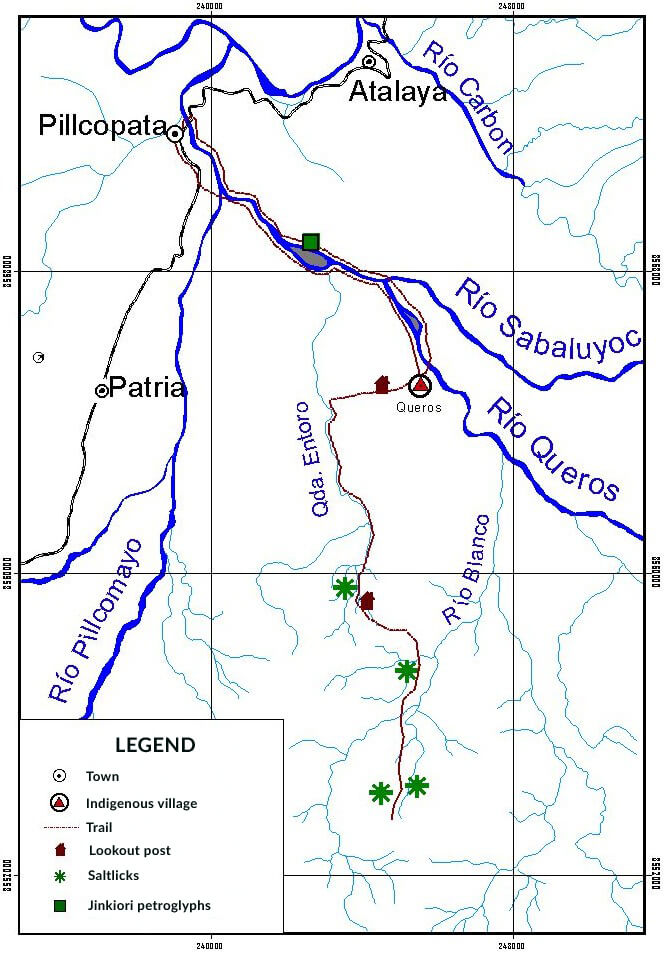

The village of Queros was legally recognised as a Native Community in 1999. The village is located on the left bank of the Queros River, approximately 11 kilometres to the southeast of the town of Pillcopata, which is about two and a half hours walking through the upper rainforest This area is characterized by a hot and humid climate, with average temperatures between 22°C and 38°C, and by abundant rainfall between November and March. The altitude ranges from 900 to 1000 metres above sea level.

Most of the soil of the village is covered by grass. The residents grow citric fruits, ice cream bean, avocado, sugar cane, and brazil nuts, among other crops, obtaining good quality products albeit in small quantities.

The majority of houses retain the traditional style of construction, built upon wooden stilts with palm roofs and using mostly natural materials. Although some houses have aluminum roofs, they prefer traditional materials because these help to keep indoor temperatures cool on hot days.

There is a one-room primary school in Queros. The community’s household water is diverted from a brook and transported to the community in tubes, but it is not purified. The community does not have a sewage system, but they do have latrines located in several places.

With regard to health, one of the inhabitants of the community has been trained as a health promoter by the Ministry of Health, although this person does not usually have the necessary medication to meet the needs of the population. The most common illnesses are gastrointestinal infections, respiratory infections, parasites and skin problem.

Illnesses are often treated using medicinal plants, as the elders and some adults in the community are familiar with a wide array of plants with medicinal properties. These plants are used to treat specific ailments, and also to restore the spiritual balance necessary for good health, letting the flow of energy that exists in all living things run its course.

Understanding this energy flow is necessary to preserve health and recover strenght. In traditional Wachiperi cosmology, the energy that makes up all living things circulates constantly. All life forms share the same beginnings and are interconnected on an underlying spiritual dimension. It is in this dimension that the distinct life cycles are developed and where disruptions of energy flows are reflected in the physical universe.

As a result of increasing contact with Western society, much of the traditional knowledge regarding medicinal plants and mythical stories has been lost, as well as perceptions about society and the environment, something which is particularly evident among the youth of the community.

As part of this westernization process, many residents of Queros have been increasingly incorporating external elements into their culture. These elements have become deeply integrated into, and even necessary to, their way of life, even if these changes may not improve their quality of life.

Many of their present activities reflect a process of adaptation to changing conditions. Traditionally, their lifestyle was based on hunting, fishing, gathering and subsistence agriculture. Nowadays, the forest’s resources are becoming more and more scarce, and they must complement their diet with products that come from outside the community.

Use of Natural Resources

In the traditional system of production, the women of the community were responsible for agriculture and the men for hunting. There were also seasonal activities, such as fishing and gathering. In recent years, the population became increasingly involved in other economic activities, such as forestry, livestock, cash crops, and arts and crafts, among others.

The local population is trying to integrate the group’s traditional perspectives and practices with their current economic needs to improve their quality of life. They have determined that their best alternative is tourism based on the cultural and natural resources of their communal territory.

The expectations of the population are to integrate the conservation of the environment with the preservation of their cultural heritage. For the people of Queros, nature is composed of spiritual entities whose origins are similar to those of human beings. Accordingly, it is necessary to maintain a good relationship with nature, using only those elements that are needed for subsistence.

Wachiperi Cosmology

For the Wachiperi, the world we live in, called Wandari, already existed when the first people appeared. The world was very similar to its current form, but there was another world above ours, called Kurundari, and a world below, called Seronhaihue, as well as other mythical places beyond human reach.

There were also distinct spiritual entities and mythical characters that influenced people’s activities, such as the beings of the river, called Waneri, and the beings of the forest, called Numberi. These beings could be good spirits (Oteri) or bad spirits (Asito), or good and bad at the same time, depending on how people behaved.

Animals possessed a spiritual dimension, and each species answered to the authority of a chief spirit, Wantopa, who also controlled the human consumption of animal meat. When hunters met with Wantopa in their dreams, this spirit could bring illness upon them as punishment, or grant them access to the animals of the forest.

The Wachiperi also believed in Amana, a great sacred rock that cured illness. People would also ask the rock to provide them with the things they needed, through the elders who could communicate with Amana. One day, however, strange people arrived who desecrated the area and touched the rock, after which Amana lost all of its beneficial properties.

People possessed an immortal spirit, which would roam through the forest, along the rivers and down the trails after death, occasionally taking the form of animals, plants or whirlpools in the water. When these spirits were bothered by the living, they were able to exert punishment.

The elders of Queros say that society was different in ancient times, but then a great catastrophe came. The few people and animals that survived are those that are alive now. The myth of Wanamei tells this story.

Wanamei : The Tree of Life

“Long ago, our ancestors did not keep track of time. They lived harmoniously and did not know death, passing most of their time protecting themselves from constant, torrential rains. But there was a time in which many changes took place, and the very survival of humanity was threatened. The Wachiperi were able to survive thanks to Wanamei, the tree of life.

The threat arose from a conflict between fire and water, expressed in the form of a gigantic fire and a great flood, that covered all of the land and annihilated entire families, as well as any people, animals and plants in their path.

The Wachiperi, however, learned that in a certain place there grew a tree called the Wanamei, in which people could take refuge from the fire and the flood.

They went in search of the tree, but upon arriving at the place where it supposedly grew, they could not find the Wanamei. Their hopes for survival faded. However, a short time later, a parrot, Jokma, appeared and offered to bring them a seed from the Wanamei if they gave him the youngest maiden among them.

The group accepted the parrot’s offer and Jokma gave them the precious seed. As soon as they planted the seed, the tree began to grow and to develop leafy branches. The remaining survivors, including people and animals, immediately climbed into the tree, but some were unable to save themselves and were burned by the flames or suffocated by the smoke.

Those that reached the highest branches were uneasy because the normal cycles of day and night had disappeared, and they were surrounded by smoke and darkness. Occasionally, when the waters or the flames drew closer, the Wachiperi asked Wanamei to grow a little more, and the tree granted their requests.

Eventually, the fire started to go out until one day it disappeared, but the ground was still hot and soft, and the inhabitants of the tree could not yet descend. The few people and animals that left the tree prematurely sank into the soil and disappeared.

So, the people had to remain in the Wanamei for an indefinite period of time. As they were so few, they married their siblings and established incestuous relationships. As a result of disobeying these rules, the people began to die. From that time onwards, people understood death as it is today.

The Wanamei was upset by the behaviour of people and began to rock back and forth to make them get down. When the tree moved, some of the people fell to the ground and could not climb up again. Many of the animals also slid out of the tree. Some time later, the birds began to fly and to explore the state of the soil, until one day they began to sing, signalling that dawn was approaching, and that a better life was returning. Then, the light appeared, but on the ground there was nothing left.

The Wachiperi, however, descended from the tree and settled on the ground once again. A short time later, some edible plants began to sprout, but as a result of this traumatic experience people grew clumsy and forgot all their previous knowledge, and this is how we have lived ever since.”

A tale by Julián Dariquebe, member of the community of Queros.

Medicinal Plants

The Wachiperi are familiar with a great variety of plants with medicinal properties, which they occasionally use to treat their diverse ailments. However, for the Wachiperi, the concept of health is not simply the absence of illness, but rather the holistic well-being of the person, including the prevention and treatment of illnesses of spiritual origin.

The following is a list of some of the most commonly used plants and their medicinal properties.

Bobinsana (Yoporo): This plant is used to ease pain in the bones, rheumatism and colds. The root of the bush is extracted and marinated into an alcoholic drink, which is later ingested in small quantities. This plant also prevents children from getting sick when infants are bathed in water mixed with bobinsana bark.

Chuchuhuasa (Chuchuhuasa): A tea prepared with the sap from the bark of this tree is used for treating rheumatic ailments, colds and to strengthen the body. Chewing pieces of the bark of this plant also helps ease toothaches and dental problems caused by cavities.

Guayaba (Kumaoi): This plant possesses anti-microbial and prophylactic properties, and it is used to treat intestinal infections. A homemade serum is prepared by boiling the stems, bark and unripe fruit, which is then ingested. Chewing regularly on the leaves of this plant also prevents cavities. The liquid from the stems is used to treat coughs, sore throats and colds associated with fever.

Sacha Culantro (Ashea): This plant is used for problems with stomach gases and belly aches, as well as to treat diarrhoea and vomiting caused by fear, especially in children. A tea of the stems and leaves is prepared and then taken by the ailing person.

Sano Sano (Misiin misiin): This plant is used to cure skin wounds by directly applying the resin from the stem to cuts and wounds. This plant is also used to treat lung, stomach and kidney problems, as well as to control haemorrhaging in women after childbirth. To treat these conditions, an infusion is prepared with the stem and is then ingested.

Wito (Oo): This plant is used by people to avoid insect bites. The liquid from the fruit is applied directly into the skin, creating a protective barrier. This liquid also promotes healing in skin wounds and acts as an antiseptic, fighting and preventing fungal infections. In addition, an infusion prepared with this fruit is used to cure coughs and respiratory infections, like bronchitis.

Yahuar Piri Piri (Masonkoropo): This plant is used to treat conjunctivitis by applying drops of the plant’s liquid to the eyes. In its liquid form it is used to treat intestinal haemorrhaging and gastric ulcers. Bruises and dislocated bones are treated by applying the crushed bulb of the plant into the affected area.

Main Attractions

The native community of Queros is one of the most welcoming villages of the area. Here, one can share a memorable moment with the villagers, who speak Spanish as well as the native language, Wachiperi. Visitors can also enjoy typical foods from the region, like pacamoto and masato, made with the meat of wild animales, fish and other products from the forest.

In their designated tourist areas, visitors can enjoy the natural landscape of the upper rainforest, with abundant wildflowers, particularly tree-like ferns and moss, as well as other species of large trees, such as cedar. These plants are found at the heart of the primary rainforest designated as a reserve within the territory of the community of Queros.

In these areas of restricted use, there are saltlicks where wild animals gather, such as peccaries, tapirs, and different species of monkeys, among other animals.

Similarly, there are places where it is possible to see large flocks of parrots, macaws, guans, falcons, caciques, cock-of-the-rock, chachalacas, doves and other species. There are also places where butterflies of diverse colours, shapes and sizes gather in great numbers.

Near Queros we also find the Ungurahui forest, a beautiful place that is part of the local ecosystem. It is also possible to see spectacled bears in this forest. The spectacled bear can climb trees and palms to great heights, but is now quite rare.

The Queros River has a great abundance of fish, which are a staple food for the residents of the village. Visitors can fish during the day and prepare a fresh dinner from their catch.

Surrounding the community, one can visit experimental plots of medicinal plants. The person responsible for cultivating those plants can explain their medical and mistical properties, and how their ancestors acquired that knowledge.

There are also interesting archaeological sights in the area. A half hour walk from the village brings the visitor to Jinkiori, a place of great spiritual significance. The Jinkiori petroglyphs are pre-Columbian drawings on an enormous rock set in the bed of the Queros River. The drawings depict geometric symbols and figures, whose meaning is not yet understood.

According to the traditional beliefs of the Wachiperi, the origin of the world, social relationships, the behaviour of the forest animals and the laws of life can all be explained through ancestral myths and legends. The residents of the community are very open to sharing their traditional values, and visitors can ask them questions about their traditional stories.

Similarly, one can ask the elders of the community to tell the story of their past conflicts with other ethnic groups and populations in their territory, the story of Apan Apan, the myth of Toto, the legends about the origin of their healing songs, and their anecdotes in the forest, among other interesting stories.

Tourist Routes

The community has a tourist shelter within the village, where visitors can stay. The Wachiperi have also identified three local tourist routes for visitors who want to hike in the forest.

The Jinkiori Tour: This is a day-long tour that consists of a three hour walk to the native community of Queros and, if one desires, a lunch based on the typical foods of the area, as well as the opportunity to share a moment with the villagers. After lunch, the visitors cross the river in a raft to visit the Jinkiori petroglyhs, returning to Pillcopata afterwards.

The Entoro Tour: This route is based on a three-day program that includes a visit to the native community of Queros, a lunch and dinner with traditional food, a visit to the medicinal plant gardens, and a night of legends and story-telling. The next day, the tour takes the visitors up the Entoro River to visit the saltlicks frequented by mammals, where visitors can also see plenty of birds. After that, visitos return to the village and then go to see the Jinkiori petroglyphs, ending their tour in Pillcopata shortly after.

The Río Blanco Tour: This route is based on a four-day program and begins with a visit to the village of Queros and its local attractions. The visitors then explore the Blanco River, visiting the mammal and butterfly saltlicks, and the Ungurahui Forest. After that, visitors return to Queros and visit the Jinkiori petraglyphs, then returning to the town of Pillcopata.

Groups of visitors can have personalized packages based on their interests and availability of time. The members of Queros who coordinate the tour programs can be contacted online, in Spanish. For additional information, please visit https://www.facebook.com/comunidad.queros

Bibliography

Dariquebe, Julián

2003 Recolección de Plantas Medicinales. Working paper.

2003 Cosmovisión Harakmbut y Creencias Huachipaeris. Working Paper, Pro-Manu Project.

Pinasco, Karina. 2002. Participacion Comunitaria en la Elaboracion del Plan de Manejo Ambiental de la Comunidad Nativa de Queros – Zona de Transicion Amazonica de la Reserva de Biosfera del Manu. Masters thesis, UNALM, Lima. 127 pgs.

Pro-Naturaleza. 1999. Proyecto Microcentral Hidroeléctrica Queros – Kosñipata. Working paper, Pro-Naturaleza.

Pro-Manu. 2002. Plan Antropológico del Parque Nacional del Manu. Working paper, Pro-Manu, Cusco, Peru.

Tello, Rodolfo. 2003. Poblaciones Indígenas de la Reserva de Biosfera del Manu. Pro-Manu, Cusco, Peru. 32 pág.

Villasante, Fritz. 2002. Aspectos Socioculturales del Parque Nacional del Manu. Working paper, Pro-Manu. Cusco, Peru.

This article, “Culture and Environment in the Native Community of Queros,” written by Rodolfo Tello, was originally published as a booklet in 2004. Pro-Manu in Cusco, Peru. 32 pages.

A more comprehensive study about the Wachiperi is currently available in book format. Click here to learn more about it.

For inquiries about visiting the Wachiperi community of Queros, and learn about their cultural traditions and environmental conservation efforts, please click here (Spanish only).